China’s once-thriving solar industry is now facing a harsh downturn. One-third of its 121 listed solar firms are now losing money. Over 50 other companies in the supply chain have already gone bankrupt this year. The recent SNEC PV Conference in Shanghai reflected this gloom, with fewer attendees and major names like Longi Green Technology and Tongwei choosing not to show up.

Solar panel prices have crashed—falling by as much as 80% from their peak in 2023. Trina Solar Chairman Gao Jifan reported that losses in solar manufacturing alone reached $40 billion, with total losses ballooning to $60 billion when other business lines are included. Most firms are now bleeding cash in a crowded market with far too much supply and not enough demand.

Stock values have also nosedived. Jinko Solar, the world’s largest panel maker by shipments, has seen shares fall nearly 30% this year in New York, and over 60% from its 2022 high. Longi, JA Solar, and Tongwei have each dropped by up to 80% in the same period.

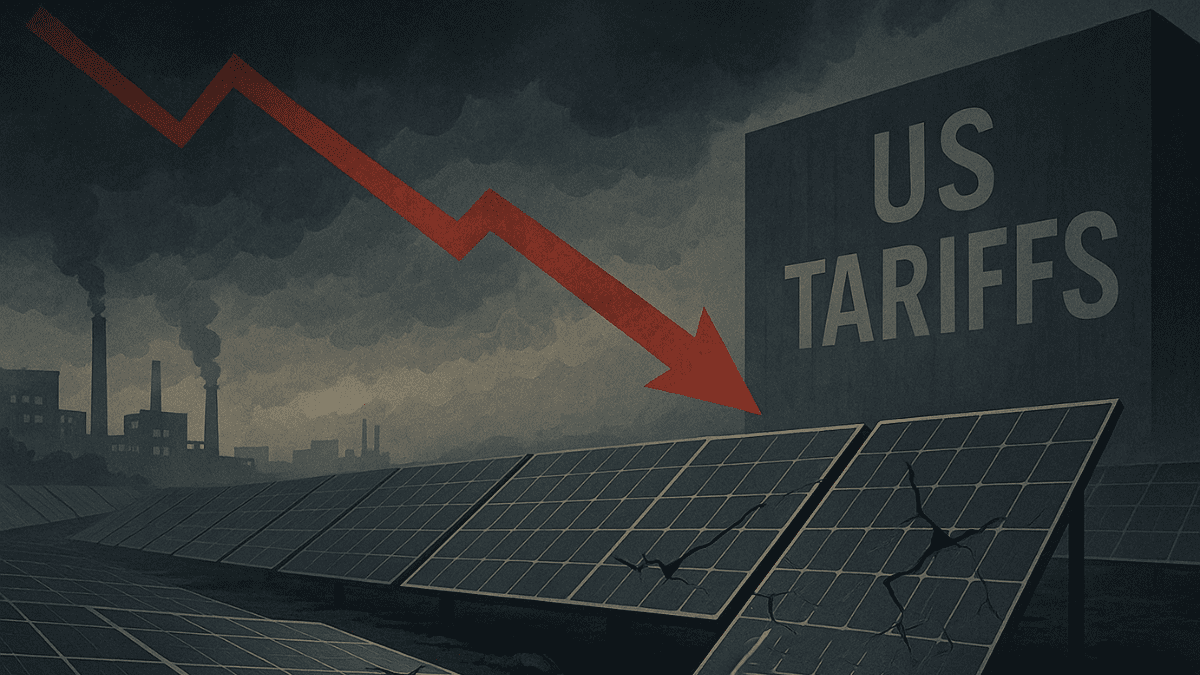

Tariffs Close Doors to the World

China still produces 80% of the world’s solar panels and components. But selling them overseas is becoming much harder. The U.S. has imposed strict tariffs not just on Chinese-made panels but also on those produced in Chinese-owned factories in Southeast Asia. As a result, China’s solar exports fell by 8% in the first quarter and dipped again in April.

China’s $50B Chip Fund Switches to Attack Mode—Targets U.S. Tech Domination in AI War

Pierre Lau, an analyst at Citigroup, noted that global demand weakened even further after the SNEC conference, dragging prices down across the board. In China, developers rushed to install panels before government incentives expired, but this front-loading means demand is expected to shrink sharply in the second half of the year.

Citigroup estimates solar installations in China could drop by 44% from the first half’s 160 gigawatts. Globally, growth is slowing too—from 87% in 2023 to an expected 10% in 2025, according to the Global Solar Council.

To fight tariffs, companies like Longi and Jinko Solar are now building factories in places like Saudi Arabia and Ethiopia. Zhang Haimeng, a vice president at Longi, explained that the U.S. remains the most profitable destination, even if the manufacturing is done elsewhere. However, moving production is not simple. Jessica Jin, an analyst at S&P Global in Shanghai, said that while assembling modules is possible abroad, the upstream steps—like silicon processing—are still hard to replicate outside China.

Desperate Diversification Amid Heavy Losses

With profits drying up, many firms are trying to enter new markets. Some, like Trina Solar and GCL Group, are building lithium battery lines to store solar energy. Others, such as Longi and Ming Yang Smart Energy, are investing in green hydrogen. But competition is fierce.

China chokes 80% of India’s fertiliser imports in silent sanctions during peak farming season

Cao Hui, general manager of REPT Battero Energy, which supplies lithium batteries for EVs and energy storage, said battery prices are falling fast—just like solar. The hydrogen sector also faces early-stage struggles and excess capacity despite government support. A manager at Shanghai-based hydrogen firm Refire admitted the sector is already suffering from deep financial losses.

Even in these new sectors, solar firms face strong rivals like EV battery giant CATL. Its founder Robin Zeng Yuqun has publicly stated his goal of becoming a complete energy provider—putting even more pressure on traditional solar companies.

Inside the industry, some leaders are calling for drastic changes. Zhu Gongshan, chairman of polysilicon giant GCL, said the industry needs “radical consolidation” to fix the oversupply. GCL’s co-CEO Lan Tianshi added that top firms are now setting up a new professional body to help control production through mergers, acquisitions, and orderly exits. Still, few large takeovers have happened. Cosimo Ries, an analyst at Trivium China, said all major firms are losing so much money that they can’t afford to buy others.

Even last year’s attempt at a price truce—where companies agreed to stick to minimum prices and quotas—failed. Shi Yonghong, a vice president at China’s Chamber of Commerce for Machinery and Electronics, said self-discipline hasn’t worked. Now, many industry leaders are urging the Chinese government to step in and bring order to the chaos.